These two

bubble pops, however will pale in comparison to the next one coming: Japanese

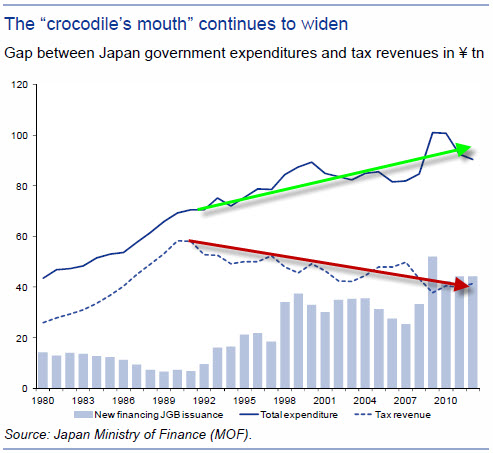

Bonds. To set a bit of context, the Japanese government, in order to stimulate

the economy back in the early 90s, had effectively begun printing money

(issuing bonds) at such a frenetic pace (and has continued unabated for the

last two decades) that the amount of government bonds issued far out-stripped

the amount of tax revenue they receive from Japanese citizens. At the moment

Japan’s government gross debt sits at 240% of GDP (More fun if we start talking

though in terms of Yen, Quadrillions of it).

While even

getting to this mark does seem logically-defying for any rational thinking

human being, what made this possible up until now were three key factors: A

large pool of savings, low interest rates, and a postive trade surplus

(earnings from exports are greater than the costs of imports).

At face

level, the following statistics could put one’s mind at ease that there is no

crisis to really worry about: Japanese have $19 trillion dollars in savings and

90% of Japanese Government Bonds are held domestically, so say if China or the

US were to decide to dump their holdings in Japanese Government Bonds, it would

not lead to a collapse in the Japanese economy. In addition overnight cash

interest rates are around 0.1% per annum, which is the lowest rate amongst all

the major central banks in the world. The below link attests this:

All good? Not quite.

Let us start

with the savings rate: During the hey-days of the late 80s and early 90s, Japan

had a savings rate of around 15 to 25%. Today it is under 3%. The two main

causes are: a) declining asset prices (i.e. deflation), and b) an ageing

population. We have effectively touched on the asset price collapse over the

last two decades with the real estate and stock market bubbles, so we will

focus on the impact of the aging population. More than 23% of Japan’s

population are above the retirement age of 65 (compare that to 11.6% in 1989),

and as the chart clearly shows below, there is a direct correlation between the

decline in the working age population and the rate of economic growth (makes

sense - less able workers, less production…).

Apart from having

a lower proportion of the population in the workforce, pension funds and

insurance companies have had to start selling their Japanese Government Bond

(JGB) holdings in order to payout the retirement benefits that are owed. This

leads to the servicability of debt becoming more difficult (seriously who wants

to put their money into savings that would only get you next to nothing in

interest?). To ascertain the degree of desperation of those governing the

finances of the nation, one “remedial” solution proposed by the new (but don’t

know for how long) finance minster Aso Taro was to ask the elderly to “hurry up

and die” http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2013/jan/22/elderly-hurry-up-die-japanese in order to reduce the cost of social welfare (18% of national income

currently, 27% by 2025) – what is the phone

number to The Hague, please?

Anyway moving

from that slightly morbid blot now is a good time to touch on interest rates, I

mean what interest rates? For about 17 or so years, the overnight cash rate in

Japan has been set by the Bank of Japan (BoJ) to under 1% per annum in order to

help revitalise the economy (see chart below).This has not quite worked out

(check out chart previously).

Now the

latest Prime Minster Shinzo Abe has promised to combat the deflation of asset

prices in Japan by proposing a 2% inflation target. This would imply making

assets, including Japanese Government Bonds more attractive to purchase. Now we

have touched on the fact that the savings rate in Japan is now under 3%, domestic

purchases would have a band-aid effect, so it would be wise to increase sales

to foreign investors, but again with a declining Yen and next to nothing

interest rates, what can make one more interested in purchasing bonds? One

solution is to increase the yield of return on Japanese Governement Bonds, but

this would imply raising interest rates.

There is a

fundamental problem to this however: Even at these low levels of interest,

25-30% of Japanese tax revenue is spent on servicing only the interest payments

for the bonds. It has been calculated that if interest rates go up to as much

as 2.5%-3.5% per annum, the tax revenue generated would not be enough to cover

the interest payments. At the moment the Japanese tax rate is 5%, with plans to

increase it to 10% by 2015, but even if all Japanese held assets were put to

service the debt issued by the Japanese government and taxes were raised to

100%, it has been forecasted that it would be enough to only service the debt

for another 12 years. Things look terminal at best.

The last

major point I want to look at is Japan’s trade surplus. Before the 2011

Earthquake/Fukushima disaster, Japan had maintained a positive trade balance

due to high volume of exports, as well as low dependency to meet the energy

requirements of the nation due to the development of nuclear reac tors.

Post

Fukushima, however, nuclear reactors were shut down leading to significnat

increases in energy imports, making Japan a net importer as oppose to a net

exporter (see chart below).

Combine that

with a weaker yen to boost exports, increased stimulus to revitalize

infrastructure (20 trillion yen promised by Shinzo Abe), falling exports to

China (it’s largest export partner, and territorial disputes brewing again) and

a downbeat global economy, it Is expected that the deficit will get much wider.

So what is it

that needs to be solved in Japan? Increase economic growth and increase the

value of asset prices. What can be done? Government go beserk, print more

money/issue more JGB at super-low interest rates and devalue Yen to increase

exports. That has been the current policy to date, and clearly has not worked..

So what about stopping the money printing, raise interest rates and increase

the value of the Yen? – As we have seen it is a quick step to sovereign

default. How about re-starting the nuclear reactors? – Not sure if one can

stomach 3-eyed fish. How about addressing xenephobic immigration policies or

increasing incentives to have larger families to increase the proportion of the

working age population? – Wishful thinking, but may be too late to implement as

it is.

If we put the

implications in a global context, consider that Japan is the third largest

economy in the world and holds $4 trillion US dollars in foreign assets. Now

mix with that the crisis in the Eurozone and Helicopter Ben Bernanke continuing

to go wild in the US with the never-ending “quantitative-easing” money printing,

we would most likely see a crisis in the Global Financial Markets unprecedented

in anyones’ time sooner rather than later.

Ah0707 - “Guns and Food (Gold and Silver too)”

No comments:

Post a Comment